Gavin Watson, un skin Place Vendôme

Une petite heure avec le photographe du Summer of Love... qui a encore du mal à s’en remettre.Interview Par Arnaud Idelon & Samuel Belfond. Toutes les photos sont de Gavin Watson représenté à Paris par la Galerie Iconoclastes.

![Spectrum – Bad to the Bone [2]](https://badtothebone.website/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/RAVING-89-LAZER-CIRCLE-0006.jpg)

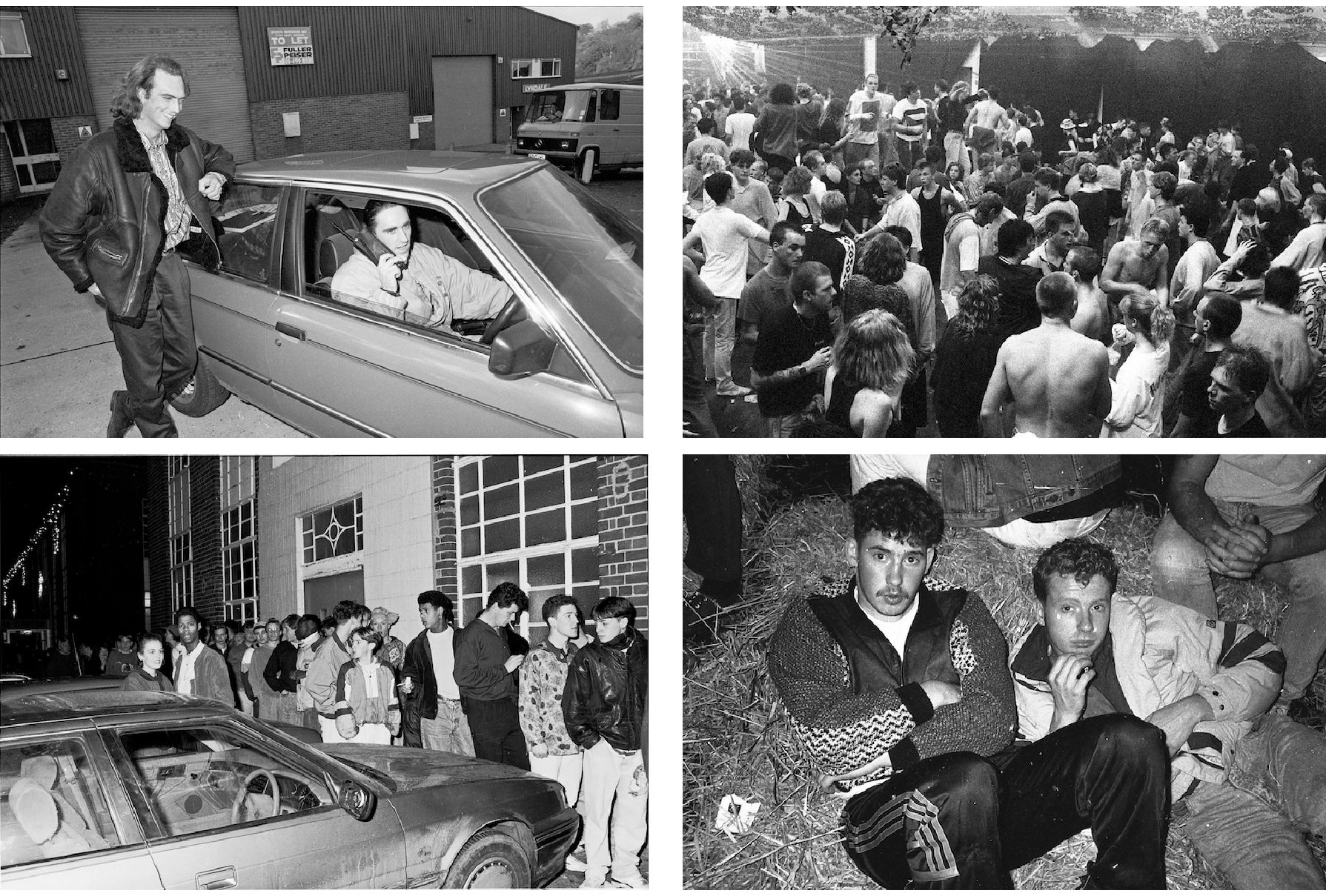

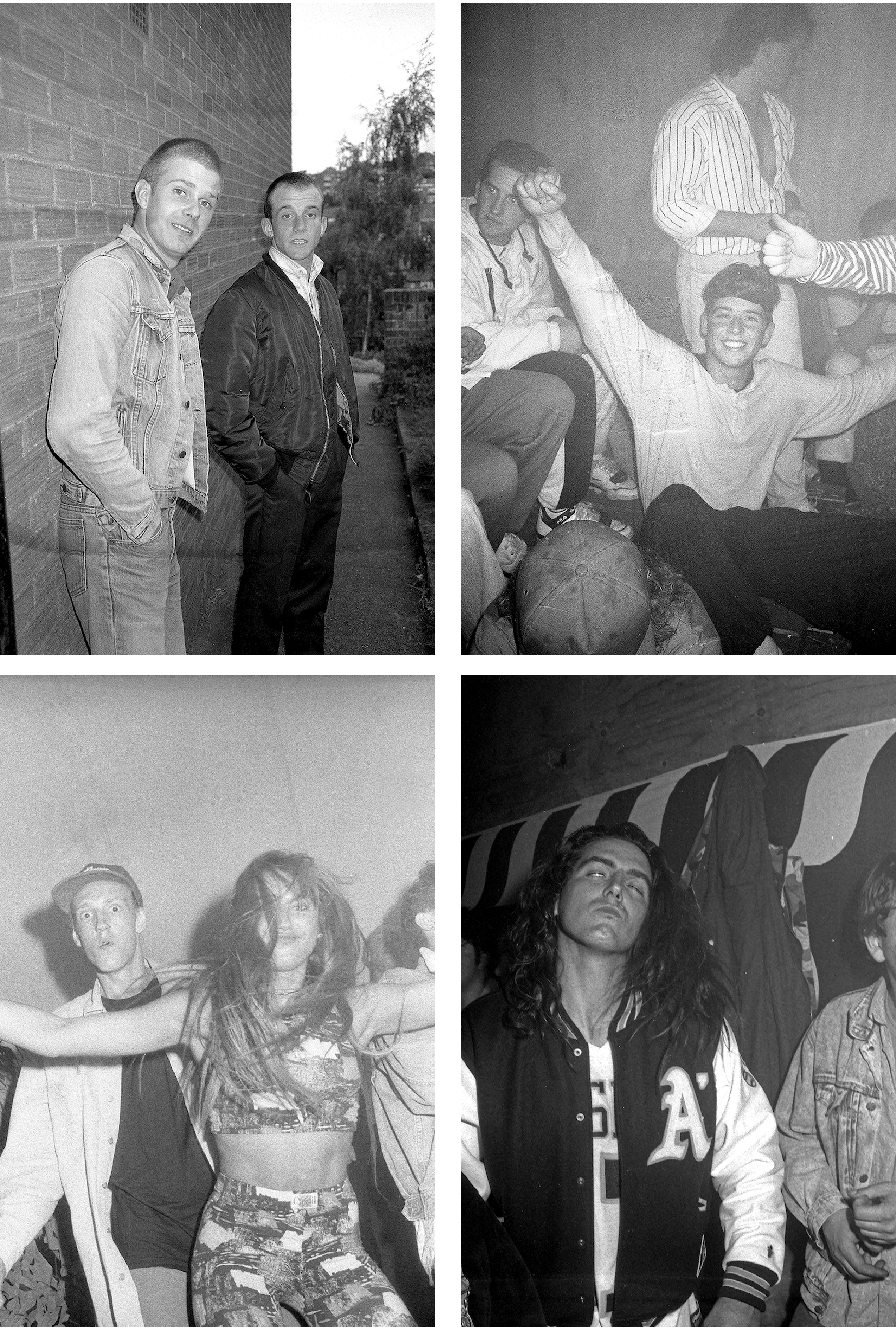

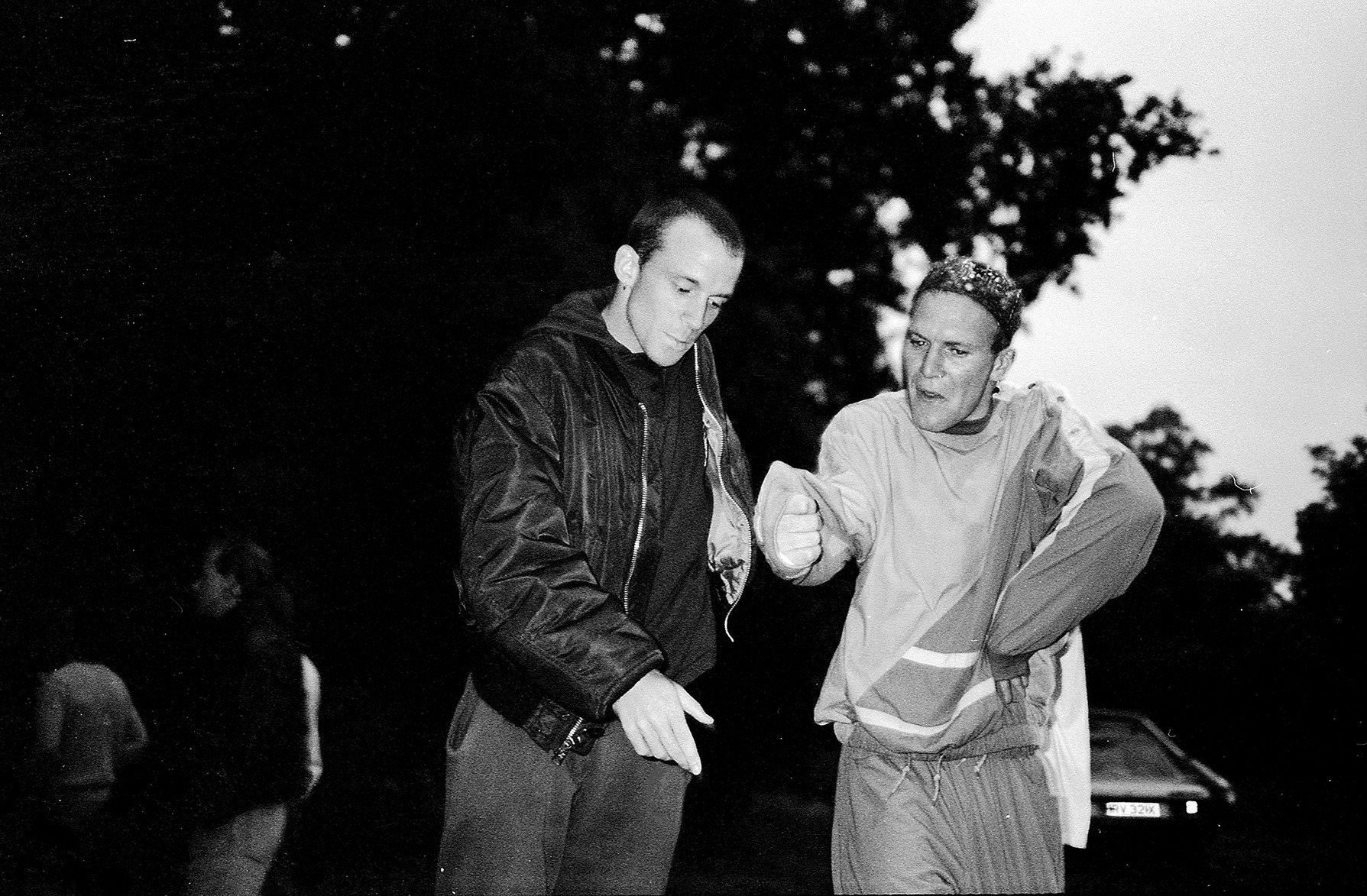

Dans le cadre de son exposition “Raving 89” à la galerie Iconoclastes, le skin puis punk puis raver Gavin Watson nous accorde une petite heure d’échanges autour d’une bouteille de Prosecco, abordant le mouvement skinhead, l’arrivée de la rave et des taz, et tous les chamboulements qu’ils entraînent dans la contre-culture britannique. On discute surtout de la fête, de la nuit et de la vie, pas beaucoup de photographie en somme. Morceaux choisis, en anglais dans le texte of course !

A : Thanks for being here and accepting this interview !

G : You’re welcome mate ! I’m privileged to be here, in this great city. I’m an old fucking skinhead from London. It’s pretty mental, for me,to be here near Givenchy, Place Vendôme.

A : We’re gonna discuss rave, skins and parties.

G : If I fucking remember what partying was like !

S : You don’t ?

G : I’m a 53 grandfather now, you don’t remember these things ! I’d be fucking dead if I had kept partying. Now you would need to take me on a fucking litter, like in the Roman time ! Being serious, these two years of partying were two years of fundamental change. I spent ten years being a skinhead, spent ten years being outside of society, took a lot of drugs, hallucinogenic, mushrooms, had some bad time on acid, and then stayed away from these drugs, after spending all this time with the hippies, with the bikers, with the drug addicts. A lot of my friend got married at eighteen, fucking eighteen ! By the time raves came in, they had a job, they had three children. We were trying to live our youth, while they were trying to be old. When rave came in, they went fucking mental, going out until six, seven, eight. There were divorces, everything broke down. Friendships, relationships, work. All the relationship we had fundamentally changed by just taking one drug once. You only had to take it once.

S : So two years were enough then.

G : Exactly. It was intense, it was enough for me. To have experienced it, to have owned it, and then to move on. In a way, it wasn’t my generation either. It was my little brother’s, who was nineteen. There wasn’t much chance for not being a skinhead, at this precise time. Initially, I’m an adventurer, I’m an outsider. Even when I was a skinhead, I was an outsider. As photographers, that’s we are, ultimately : outsiders and observers. I felt really deeply that something had came to an end. The way I translated that was that I needed to grow up. I was 23, in the working class environment I should have been married by then. So the skinhead era was coming to an end. We were all to get married, to get children. You cannot be a skinhead forever. But, there was also this feeling, deep inside, that I was not ready yet !

S: How did it all started ? How did you became a photographer ?

G : I just picked up a camera at fourteen. One day, I went to buy binoculars, to see the moon better - that’s kind of weird kid I was - and went to the shop with my Christmas money, and then I saw a camera. I bought it, then one day I got my first picture back, and I decided that I would be a photographer. That was literally it. There was no thought about doing anything else. Which is good and bad. I do thank the Lord that I found it, found who I was that early. God knows what would have happened if I didn’t.

S : You don’t ?

G : I’m a 53 grandfather now, you don’t remember these things ! I’d be fucking dead if I had kept partying. Now you would need to take me on a fucking litter, like in the Roman time ! Being serious, these two years of partying were two years of fundamental change. I spent ten years being a skinhead, spent ten years being outside of society, took a lot of drugs, hallucinogenic, mushrooms, had some bad time on acid, and then stayed away from these drugs, after spending all this time with the hippies, with the bikers, with the drug addicts. A lot of my friend got married at eighteen, fucking eighteen ! By the time raves came in, they had a job, they had three children. We were trying to live our youth, while they were trying to be old. When rave came in, they went fucking mental, going out until six, seven, eight. There were divorces, everything broke down. Friendships, relationships, work. All the relationship we had fundamentally changed by just taking one drug once. You only had to take it once.

S : So two years were enough then.

G : Exactly. It was intense, it was enough for me. To have experienced it, to have owned it, and then to move on. In a way, it wasn’t my generation either. It was my little brother’s, who was nineteen. There wasn’t much chance for not being a skinhead, at this precise time. Initially, I’m an adventurer, I’m an outsider. Even when I was a skinhead, I was an outsider. As photographers, that’s we are, ultimately : outsiders and observers. I felt really deeply that something had came to an end. The way I translated that was that I needed to grow up. I was 23, in the working class environment I should have been married by then. So the skinhead era was coming to an end. We were all to get married, to get children. You cannot be a skinhead forever. But, there was also this feeling, deep inside, that I was not ready yet !

S: How did it all started ? How did you became a photographer ?

G : I just picked up a camera at fourteen. One day, I went to buy binoculars, to see the moon better - that’s kind of weird kid I was - and went to the shop with my Christmas money, and then I saw a camera. I bought it, then one day I got my first picture back, and I decided that I would be a photographer. That was literally it. There was no thought about doing anything else. Which is good and bad. I do thank the Lord that I found it, found who I was that early. God knows what would have happened if I didn’t.

G : You’re welcome mate ! I’m privileged to be here, in this great city. I’m an old fucking skinhead from London. It’s pretty mental, for me,to be here near Givenchy, Place Vendôme.

A : We’re gonna discuss rave, skins and parties.

G : If I fucking remember what partying was like !

S : You don’t ?

G : I’m a 53 grandfather now, you don’t remember these things ! I’d be fucking dead if I had kept partying. Now you would need to take me on a fucking litter, like in the Roman time ! Being serious, these two years of partying were two years of fundamental change. I spent ten years being a skinhead, spent ten years being outside of society, took a lot of drugs, hallucinogenic, mushrooms, had some bad time on acid, and then stayed away from these drugs, after spending all this time with the hippies, with the bikers, with the drug addicts. A lot of my friend got married at eighteen, fucking eighteen ! By the time raves came in, they had a job, they had three children. We were trying to live our youth, while they were trying to be old. When rave came in, they went fucking mental, going out until six, seven, eight. There were divorces, everything broke down. Friendships, relationships, work. All the relationship we had fundamentally changed by just taking one drug once. You only had to take it once.

S : So two years were enough then.

G : Exactly. It was intense, it was enough for me. To have experienced it, to have owned it, and then to move on. In a way, it wasn’t my generation either. It was my little brother’s, who was nineteen. There wasn’t much chance for not being a skinhead, at this precise time. Initially, I’m an adventurer, I’m an outsider. Even when I was a skinhead, I was an outsider. As photographers, that’s we are, ultimately : outsiders and observers. I felt really deeply that something had came to an end. The way I translated that was that I needed to grow up. I was 23, in the working class environment I should have been married by then. So the skinhead era was coming to an end. We were all to get married, to get children. You cannot be a skinhead forever. But, there was also this feeling, deep inside, that I was not ready yet !

S: How did it all started ? How did you became a photographer ?

G : I just picked up a camera at fourteen. One day, I went to buy binoculars, to see the moon better - that’s kind of weird kid I was - and went to the shop with my Christmas money, and then I saw a camera. I bought it, then one day I got my first picture back, and I decided that I would be a photographer. That was literally it. There was no thought about doing anything else. Which is good and bad. I do thank the Lord that I found it, found who I was that early. God knows what would have happened if I didn’t.

S : You don’t ?

G : I’m a 53 grandfather now, you don’t remember these things ! I’d be fucking dead if I had kept partying. Now you would need to take me on a fucking litter, like in the Roman time ! Being serious, these two years of partying were two years of fundamental change. I spent ten years being a skinhead, spent ten years being outside of society, took a lot of drugs, hallucinogenic, mushrooms, had some bad time on acid, and then stayed away from these drugs, after spending all this time with the hippies, with the bikers, with the drug addicts. A lot of my friend got married at eighteen, fucking eighteen ! By the time raves came in, they had a job, they had three children. We were trying to live our youth, while they were trying to be old. When rave came in, they went fucking mental, going out until six, seven, eight. There were divorces, everything broke down. Friendships, relationships, work. All the relationship we had fundamentally changed by just taking one drug once. You only had to take it once.

S : So two years were enough then.

G : Exactly. It was intense, it was enough for me. To have experienced it, to have owned it, and then to move on. In a way, it wasn’t my generation either. It was my little brother’s, who was nineteen. There wasn’t much chance for not being a skinhead, at this precise time. Initially, I’m an adventurer, I’m an outsider. Even when I was a skinhead, I was an outsider. As photographers, that’s we are, ultimately : outsiders and observers. I felt really deeply that something had came to an end. The way I translated that was that I needed to grow up. I was 23, in the working class environment I should have been married by then. So the skinhead era was coming to an end. We were all to get married, to get children. You cannot be a skinhead forever. But, there was also this feeling, deep inside, that I was not ready yet !

S: How did it all started ? How did you became a photographer ?

G : I just picked up a camera at fourteen. One day, I went to buy binoculars, to see the moon better - that’s kind of weird kid I was - and went to the shop with my Christmas money, and then I saw a camera. I bought it, then one day I got my first picture back, and I decided that I would be a photographer. That was literally it. There was no thought about doing anything else. Which is good and bad. I do thank the Lord that I found it, found who I was that early. God knows what would have happened if I didn’t.

A : And your first subjects were your mates ?

G : Yeah, absolutely. The year after I got my first camera, the skinhead thing exploded and it was incredible ! My friends were incredible, life was incredible, women were too. That’s only a while after we were told that skinheads were nazis. My friends and I, we were looking at each other, wondering : « where are these nazis they are talking about ? ». It was just made up, in the beginning. But then people really became nazis, because people were damaged, angry, threatened. They read things in the Time, or in the big foreign newspapers, and they decided they would became one these nazis newspaper were talking about. All of a sudden, something that came from Jamaica and Mods, a true subculture of black and white people coming together, West Indians and British coming together, just vanished, as people started thinking skinheads were just nazis.

A : Do you consider yourself a British subculture historian ?

G : No, I don’t. I just lived it. The only reason these photographs exist is because I wanted to be there, and I loved it. I happened to take pictures, and then I got given that label. I don’t really fit In. I’m not a documentary photographer, even so I am a documentary photographer. At this time, there was no newspaper, no story for me to follow. Just pictures of these kids on drugs, photographs of skinheads beating each other up. What they wanted the peasants to know. I just told the true story. But it was not appreciated at the time.

S : You say you are not a documentary photographer, but yet you say you are. What is your position toward that ?

G : I just became one as time went on. Originally, these pictures were just photographs of my friends. If you take a photograph of your friend, and then show it to the newspaper, they will have no interest in it. But if you show it twenty years later, it becomes of interest. Back in these times, 1984, nobody liked skinheads. But later, somebody saw these pictures and decided they were brilliant. Times just changed. And just then I started getting called a documentary photographer. I had just documented my friends.

A : You were the kind of perfect Londoner, at this time. Were you aware of what was going on elsewhere in England : In Manchester, in Liverpool ?

G : When you were in a gang, with no mobile phones at these times, you just knew where all the other gangs were, you just did. It was a really small world. From 1977 to 1981 when it became massive. Then, hip hop came in, and all the black kids went to hip hop because it was safe. When I first published my book, in 1984, it was only for a skinhead community that was small again. This is something that is often untold, but most of the time people just went to becoming skinheads because of the nazi thing, and then discovered the culture, the music that was beneath it. A lot of men went into that and just then understood there was a massive culture to discover.

A : What was being a skinhead at this time ?

G : It is a combination of a lot of thing. All I know, it is that wherever you find a strong working class, be it in China, in Indonesia, in Mexico, you will find skinheads. It speaks to something deeper. It answers to the insecurity of youth, with some sort of brotherhood for young men that need pride. It is tribal, so it speaks to the tribal part of yourself.

A : Then came dance music and extasy.

G : It was unbelievable. Before that the world was divided. There were skins, there were blacks, there were football hooligans. Every weekend was extremely violent, a scary place to be. Some people, that had the energy, started to put on raves, because it was a safer place to be and party. And they made a fortune out of it. This was all about creating a place where no one was fighting. When ecstasy came, it just washed away all these divisions. Then cocaine came in, and the divisions came back. But for some years we learned what it was to be unified, a unified nation. It wasn’t just raving, actually, but a whole Zeitgeist. The Wall came down, there was a massive wave that spread across Europe, and that was expressed through dancing, that was all about ignoring the law.

A : You were talking about a « unified nation », do you consider that raving was political ?

G : It became political. And that is because they were vastly outdated laws in place that just had no relevance anymore. They were curfews at 10pm on weekend nights, that were edited during WWI ! Can you imagine ? They were still trying to apply these laws in 1989 and people just went : « fuck off » ! It was not political, it was much more spontaneous in the beginning. And this worked because it was not driven solely by working class. Had it been working class only, they would have stomped it. But it wasn’t. It was a movement that went all the way from working class to Lords. Even politicians were there, even if they were trying to pretend they were not. They were even rumors that all this, raving, was part of a social experiment : release the drug and see what happens.

G : Yeah, absolutely. The year after I got my first camera, the skinhead thing exploded and it was incredible ! My friends were incredible, life was incredible, women were too. That’s only a while after we were told that skinheads were nazis. My friends and I, we were looking at each other, wondering : « where are these nazis they are talking about ? ». It was just made up, in the beginning. But then people really became nazis, because people were damaged, angry, threatened. They read things in the Time, or in the big foreign newspapers, and they decided they would became one these nazis newspaper were talking about. All of a sudden, something that came from Jamaica and Mods, a true subculture of black and white people coming together, West Indians and British coming together, just vanished, as people started thinking skinheads were just nazis.

A : Do you consider yourself a British subculture historian ?

G : No, I don’t. I just lived it. The only reason these photographs exist is because I wanted to be there, and I loved it. I happened to take pictures, and then I got given that label. I don’t really fit In. I’m not a documentary photographer, even so I am a documentary photographer. At this time, there was no newspaper, no story for me to follow. Just pictures of these kids on drugs, photographs of skinheads beating each other up. What they wanted the peasants to know. I just told the true story. But it was not appreciated at the time.

S : You say you are not a documentary photographer, but yet you say you are. What is your position toward that ?

G : I just became one as time went on. Originally, these pictures were just photographs of my friends. If you take a photograph of your friend, and then show it to the newspaper, they will have no interest in it. But if you show it twenty years later, it becomes of interest. Back in these times, 1984, nobody liked skinheads. But later, somebody saw these pictures and decided they were brilliant. Times just changed. And just then I started getting called a documentary photographer. I had just documented my friends.

A : You were the kind of perfect Londoner, at this time. Were you aware of what was going on elsewhere in England : In Manchester, in Liverpool ?

G : When you were in a gang, with no mobile phones at these times, you just knew where all the other gangs were, you just did. It was a really small world. From 1977 to 1981 when it became massive. Then, hip hop came in, and all the black kids went to hip hop because it was safe. When I first published my book, in 1984, it was only for a skinhead community that was small again. This is something that is often untold, but most of the time people just went to becoming skinheads because of the nazi thing, and then discovered the culture, the music that was beneath it. A lot of men went into that and just then understood there was a massive culture to discover.

A : What was being a skinhead at this time ?

G : It is a combination of a lot of thing. All I know, it is that wherever you find a strong working class, be it in China, in Indonesia, in Mexico, you will find skinheads. It speaks to something deeper. It answers to the insecurity of youth, with some sort of brotherhood for young men that need pride. It is tribal, so it speaks to the tribal part of yourself.

A : Then came dance music and extasy.

G : It was unbelievable. Before that the world was divided. There were skins, there were blacks, there were football hooligans. Every weekend was extremely violent, a scary place to be. Some people, that had the energy, started to put on raves, because it was a safer place to be and party. And they made a fortune out of it. This was all about creating a place where no one was fighting. When ecstasy came, it just washed away all these divisions. Then cocaine came in, and the divisions came back. But for some years we learned what it was to be unified, a unified nation. It wasn’t just raving, actually, but a whole Zeitgeist. The Wall came down, there was a massive wave that spread across Europe, and that was expressed through dancing, that was all about ignoring the law.

A : You were talking about a « unified nation », do you consider that raving was political ?

G : It became political. And that is because they were vastly outdated laws in place that just had no relevance anymore. They were curfews at 10pm on weekend nights, that were edited during WWI ! Can you imagine ? They were still trying to apply these laws in 1989 and people just went : « fuck off » ! It was not political, it was much more spontaneous in the beginning. And this worked because it was not driven solely by working class. Had it been working class only, they would have stomped it. But it wasn’t. It was a movement that went all the way from working class to Lords. Even politicians were there, even if they were trying to pretend they were not. They were even rumors that all this, raving, was part of a social experiment : release the drug and see what happens.

S : From mods to skinhead, and then raving, do you consider we went into some sort of feminization of youth culture ?

G : I don’t think it was a feminine energy, but definitely a softening up of youth culture, a brotherhood energy. The drug helped overcome the suppressed part of being British, getting more affectionate with each other, like the Latin European countries. You could expressed your masculinity with dancing. Before that, we were just standing, in discos, looking at girls, still standing, and then getting into a fight ! Even though you had three kids home men wanted to have that Friday night with a fight. This is why all this could have only had happened in England, because of the way we are so suppressed in that country. You know, forty years it was inconceivable to eat garlic, because it was a French thing ! That’s how we were back then. Things have definitely changed.

S : What was the motivation for ravers ? Was it about challenging the authority ?

G : No, it was just normal kids. We skinheads were rebels, we were fighting the police. These normal kids had normal families, normal jobs. It became political because the laws had to change, a law that was forbidding partying and existed since 1914. The motivation was just about having a party on Friday, having the right contact, and going there ! And actually the police was happy : everything was gone and out of town ! No one was drunk, fighting just stopped. What could they do anyway with the ravers ? 40 000 people turning up, what could they do except bringing the army ? Then the government got together, they tried to ban it, it was so sad and silly. How can you fucking ban the ocean ? They actually did the greatest thing : they made it official and opened a club. The moment the Ministry of Sound opened, this was over. You just had to go ever, do MDMA, boom, but it was gone. Spiral Tribe then took because they were a bunch of hippies and really out of society for years.

S : So the club was an attempt to regulate ?

G : Of course. But let’s be honest, you cannot have massive illegal parties going on all over England for years. People had to go to work ! Like all revolution, rave happened in its purity. In the beginning, it was just about rave music. Three years later there was techno, there was gabber, Detroit house, and so on, and divisions came back. But we witnessed a pure time before that.

S : Did you have any sense, as a photographer, of the way you wanted to capture that purity ?

G : No, I hated it. I did not want to take the camera, did not want to take those photographs. When I got the photographs back I fucking hated then, put them in a box for years. The reason I took those photographs is because it got me there for free. Before that, I had spent two years travelling across Europe taking photographs of bands for a magazine. And all I wanted to do was going raving ! I had to go these raves, with a fucking Nikon, everyone was paranoid because of the dugs everywhere. But as I had been a skinhead for 10 years, I was like, whatever. But I did not want to take these photographs. It just happened the promoters started to use them for flyers. So I had to take photos. I did some in the beginning of the party, left the camera away, went dancing, and just took a few more at the end of the night ! But I never wondered about technical specs or shit, I just took shots and went on. At some point, someone saw these photos and went got really interested in them, and I ended up to like them. Now I can see what they mean ?

S : What do think about that rave revival we are seeing today, especially in France ?

G : It might be a thirty year pattern, something that is just in the air. People just dig into that because this was the last authentic movement that did not come from a fucking marketing campaign to sell you a pair of fucking Nikes. They were eventually to re-ash it anyway. After re-ashing rock, punk, skinheads. Authenticity does not seem to be a thing anymore.

S : At some point, we need to find again this authenticity in raving.

G : It is called recession, mate. A real one. These things come out of hard times. You look at nearly every sub-culture and you see each of them is a « fuck you » to something. Hells Angels was a « fuck you » to having nothing to come back to after the war. Skinheads were a « fuck you » to the hippies. Now everything safe, we live in a Benetton world.

S : Are these times too Benetton for raving ?

G : I think raving led to Benetton times. What was positive twenty years ago is now negative. Everybody was defined, and then you could just wear anything, no labels anymore, no star, no popstar, no Rolling Stones, no Beatles. That is the purity of it. And people could not really make money out of it. It was too fluid. No one gave a fuck about DJs. Everybody was dancing together, no one wanted to look at the DJ.

A : We have one finale question, why do you party, and why do people party ?

G : That is a deep fucking anthropological question. My theory is : it is fucking tough living. So we got these cigarettes, and we need to go nuts once a month, and that’s what every tribe in the world is doing. When I’m gonna die one day, when you feel all that pressure, all these responsibilities, at some point you need to release and go nuts. Then another month goes on, but you had that release. Humanity needs to let go of this absolute terror of living.

G : I don’t think it was a feminine energy, but definitely a softening up of youth culture, a brotherhood energy. The drug helped overcome the suppressed part of being British, getting more affectionate with each other, like the Latin European countries. You could expressed your masculinity with dancing. Before that, we were just standing, in discos, looking at girls, still standing, and then getting into a fight ! Even though you had three kids home men wanted to have that Friday night with a fight. This is why all this could have only had happened in England, because of the way we are so suppressed in that country. You know, forty years it was inconceivable to eat garlic, because it was a French thing ! That’s how we were back then. Things have definitely changed.

S : What was the motivation for ravers ? Was it about challenging the authority ?

G : No, it was just normal kids. We skinheads were rebels, we were fighting the police. These normal kids had normal families, normal jobs. It became political because the laws had to change, a law that was forbidding partying and existed since 1914. The motivation was just about having a party on Friday, having the right contact, and going there ! And actually the police was happy : everything was gone and out of town ! No one was drunk, fighting just stopped. What could they do anyway with the ravers ? 40 000 people turning up, what could they do except bringing the army ? Then the government got together, they tried to ban it, it was so sad and silly. How can you fucking ban the ocean ? They actually did the greatest thing : they made it official and opened a club. The moment the Ministry of Sound opened, this was over. You just had to go ever, do MDMA, boom, but it was gone. Spiral Tribe then took because they were a bunch of hippies and really out of society for years.

S : So the club was an attempt to regulate ?

G : Of course. But let’s be honest, you cannot have massive illegal parties going on all over England for years. People had to go to work ! Like all revolution, rave happened in its purity. In the beginning, it was just about rave music. Three years later there was techno, there was gabber, Detroit house, and so on, and divisions came back. But we witnessed a pure time before that.

S : Did you have any sense, as a photographer, of the way you wanted to capture that purity ?

G : No, I hated it. I did not want to take the camera, did not want to take those photographs. When I got the photographs back I fucking hated then, put them in a box for years. The reason I took those photographs is because it got me there for free. Before that, I had spent two years travelling across Europe taking photographs of bands for a magazine. And all I wanted to do was going raving ! I had to go these raves, with a fucking Nikon, everyone was paranoid because of the dugs everywhere. But as I had been a skinhead for 10 years, I was like, whatever. But I did not want to take these photographs. It just happened the promoters started to use them for flyers. So I had to take photos. I did some in the beginning of the party, left the camera away, went dancing, and just took a few more at the end of the night ! But I never wondered about technical specs or shit, I just took shots and went on. At some point, someone saw these photos and went got really interested in them, and I ended up to like them. Now I can see what they mean ?

S : What do think about that rave revival we are seeing today, especially in France ?

G : It might be a thirty year pattern, something that is just in the air. People just dig into that because this was the last authentic movement that did not come from a fucking marketing campaign to sell you a pair of fucking Nikes. They were eventually to re-ash it anyway. After re-ashing rock, punk, skinheads. Authenticity does not seem to be a thing anymore.

S : At some point, we need to find again this authenticity in raving.

G : It is called recession, mate. A real one. These things come out of hard times. You look at nearly every sub-culture and you see each of them is a « fuck you » to something. Hells Angels was a « fuck you » to having nothing to come back to after the war. Skinheads were a « fuck you » to the hippies. Now everything safe, we live in a Benetton world.

S : Are these times too Benetton for raving ?

G : I think raving led to Benetton times. What was positive twenty years ago is now negative. Everybody was defined, and then you could just wear anything, no labels anymore, no star, no popstar, no Rolling Stones, no Beatles. That is the purity of it. And people could not really make money out of it. It was too fluid. No one gave a fuck about DJs. Everybody was dancing together, no one wanted to look at the DJ.

A : We have one finale question, why do you party, and why do people party ?

G : That is a deep fucking anthropological question. My theory is : it is fucking tough living. So we got these cigarettes, and we need to go nuts once a month, and that’s what every tribe in the world is doing. When I’m gonna die one day, when you feel all that pressure, all these responsibilities, at some point you need to release and go nuts. Then another month goes on, but you had that release. Humanity needs to let go of this absolute terror of living.

Photographer : Gavin Watson – Text : Arnaud Idelon & Samuel Belfond